‘Healthy Privilege’ – When You Just Can’t Imagine Being Sick

| May 6, 2013

Have you had the experience of knowing something intuitively, but without realizing that the thing you know already has a name? For example, have you ever found yourself limping along on the losing end of an argument, yet only much later (when it was far too late!) you suddenly thought of just the perfectly witty retort that you should have come up with earlier?

There’s a name for that. The French call this ‘l’esprit d’escalier’, literally “the spirit of the staircase”. You’re welcome.

Similarly, I’ve been writing for some time about my niggling frustration over something else that I didn’t even realize had an actual name.

It all started last fall when I met a group of young (healthy! fit! not-sick!) tech-savvy hypemeisters in the heart of Silicon Valley while attending Stanford University’s Medicine X conference as an ePatient scholar. These folks seemed very busy designing, developing and securing venture capital funding for their health tech startup companies – each of which was destined, of course, to be the Next Big Thing in technology.

The more hypemeisters I met, the more niggling my frustration became, mostly because their self-tracking mobile health apps didn’t seem to have Real Live Patients like me in mind. Instead, their target market appeared to be what doctors call the “worried well”, like many of those in the Quantified Self movement.

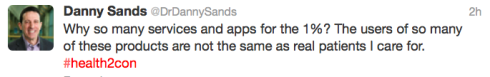

For example, during the Health 2.0 conference in San Francisco last fall, Dr. Danny Sands (founder and former president of the Society for Participatory Medicine) tweeted this:

It struck me that the imaginary patient using this technology wasn’t anything like me, or my readers, or most of the heart patients I meet or hear from or talk to on any given day. Instead, the patient that the hypemeisters talked about seemed to be some kind of fairy tale fantasy patient: tech-savvy, highly motivated, compliant, eager to track every possible health indicator 24/7, and most of all – oh, did I mention? – NOT SICK!

The pervasive attitude of the hypemeisters seemed to be that they – and they alone – could transform patient engagement, the entire health care system, and possibly life on this planet as we know it through the sheer brilliance of their health app/device/technology.

Turns out, there’s a name for that attitude. I was gobsmacked to learn this particular name recently from Dr. Ann Becker-Schutte. She’s a counseling psychologist in Kansas City who explained the concept like this:

“Many physical health conditions and all mental health conditions fall into the category of 'invisible illness'…That means someone who is casually looking at you might not be able to see the level of pain you experience. And they probably don’t understand the effort that goes into a ‘normal’ day…They don’t see or understand because they have some degree of what I am calling ‘healthy privilege‘."

Eureka! She was describing the hypemeisters! But she could also be describing (healthy) family members, or (healthy) friends, or (healthy) work colleagues, or (healthy) care providers who may be well-meaning, but just don’t get it.

Dr. Becker-Schutte also adapted the definition of healthy privilege from Kendall Clark’s definition of white privilege, like so:

“Healthy privilege”:

- a. A right, advantage, or immunity granted to or enjoyed by healthy persons beyond the common advantage of all others; an exemption in many particular cases from certain burdens or liabilities.

b. A special advantage or benefit of healthy persons; explained by reference to divine dispensations, natural advantages, gifts of fortune, genetic endowments, social relations, etc. - A privileged position; the possession of an advantage healthy persons enjoy over persons with illness.

- The special right or immunity attaching to healthy persons as a social relation; prerogative.

In addition to that formal definition, Dr. Becker-Schutte added this:

“Healthy people enjoy the privilege of bodies that work in the ways that they expect, free from regular pain or suffering, without extraordinary effort…Healthy privilege allows healthy people to assume that their experience is ‘normal’, and to be unaware that coping strategies that work for them will not work for someone dealing with illness.”

What this means in everyday life is that there’s a big fat difference, for example, between a highly engaged community that enthusiastically uses technology to track daily health indicators like weight/mood/motivation/sex life/food/exercise/activities/sleep, and actual real live sick people coping with a debilitating chronic disease every day who may lack the energy, ability or will to commit to self-tracking technology in any kind of meaningful fashion.

And I am one of them. I do consider myself an engaged patient, but I do not own a smartphone, a 7-inch tablet, or an iPad – nor, as a person with a chronic illness living on a modest disability pension, could I afford them. My idea of self-tracking is putting a sticker on a little bathroom cabinet calendar for each day I’m able to exercise.

It’s been said that coping with a chronic illness every day can in itself feel so overwhelming that being expected to embrace an extra task like self-tracking is simply too much. It’s what Dr. Victor Montori and his Mayo Clinic-based team call “the burden of treatment” in their important work with chronic illness and Minimally Disruptive Medicine.

But this reality must sound foreign to those living with the luxury that healthy privilege provides. I think one of the reasons that the concept of healthy privilege had such a profound impact on me was that, until I survived a heart attack in 2008, I too had been fairly bursting with that sense of healthy privilege myself.

I knew nothing about what it might be like to live with a chronic and progressive disease every day of my life – and why would I? I’d been a distance runner for 19 years. I was a busy, active, healthy person with a career I loved and many family, community and social events penciled into my bulging calendar. And even though I worked in hospice palliative care – so saw firsthand countless patients and families dealing with end-stage disease over the years – observing an ill person in bed means nothing in terms of understanding what “ill” feels like.

What I’ve learned since my heart attack is that, until you or somebody you care about are personally affected by a life-altering diagnosis, it’s almost impossible to really get what being sick every day actually means.

Such is the bliss – and the ignorance – of healthy privilege.

This blog was originally published on the Heart Sisters blog April 13, 2013.